Table of Contents

The terms wealth manager and financial advisor are widely used across the financial industry, but they are not legal designations. No regulator licenses someone simply as a “wealth manager” or “financial advisor.” These titles can be adopted regardless of credentials, registration status, or fiduciary obligation. As a result, understanding the real difference requires looking beyond titles and examining regulatory status, scope of services, compensation structure, and governance practices.

This distinction matters most for investors with increasing complexity, concentrated portfolios, business interests, tax exposure, or estate planning needs—where the quality of advice and ongoing oversight can materially affect outcomes.

Definitions and Regulatory Context

“Financial advisor” is a broad, non-specific term. It can refer to:

Some financial advisors operate under a fiduciary standard, while others are governed by Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI), which applies to brokers at the transaction level. The title alone does not indicate which framework applies.

“Wealth manager” is most commonly used by professionals serving high-net-worth (HNW) or ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) clients. In practice, wealth managers are often RIAs operating under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which imposes a continuous fiduciary duty of loyalty and care.

Industry bodies such as the CFA Institute describe private wealth management as the integration of:

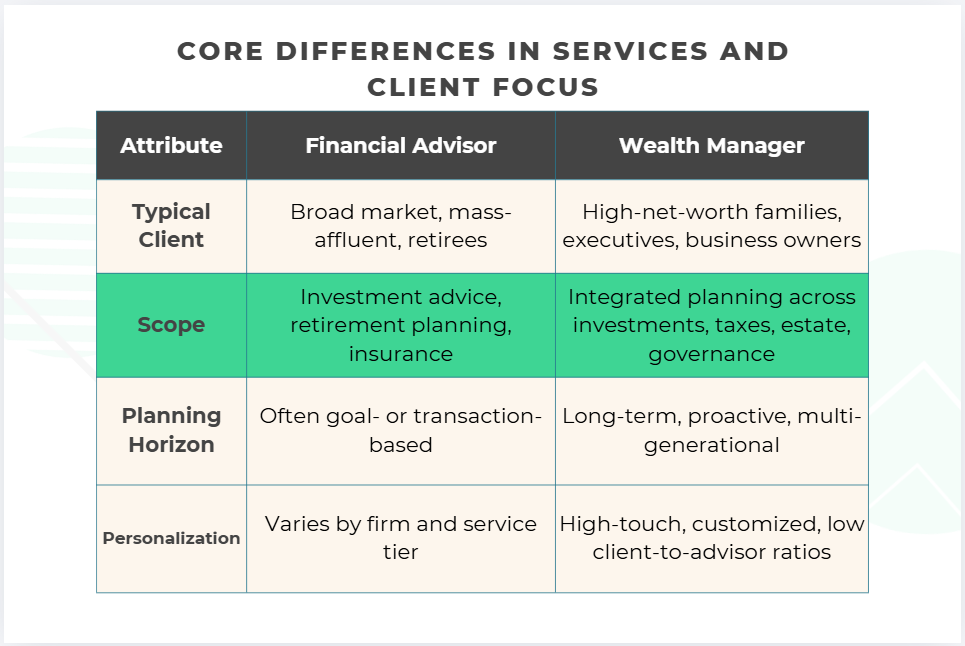

Financial advisors typically respond to client-initiated needs—saving for retirement, selecting investments, or planning for education expenses. Wealth managers are structured to anticipate complexity and coordinate across multiple domains of a client’s financial life.

Financial advisors may be compensated through:

Wealth managers, by contrast, almost always use asset-based or fixed fee-only models, particularly for portfolios above $1–5 million. This structure reduces product-driven conflicts and aligns compensation with long-term portfolio stewardship rather than transactional activity.

A defining feature of wealth management is formal governance.

For investors, this distinction affects:

As portfolios grow in size and complexity, risk increasingly comes not from broad market movements alone, but from specific events—regulatory actions, earnings shocks, executive changes, or industry disruptions. Traditional periodic reviews may not fully capture these dynamics.

Some wealth managers have adapted by incorporating systematic, data-driven monitoring into their fiduciary process. For example, Michael Flatley represents a model in which professional judgment is paired with structured analytics to improve situational awareness across managed accounts.

Rather than relying solely on discretionary review cycles, tools such as LevelFields are used as analytical infrastructure. These systems evaluate how stocks have historically reacted to defined corporate and macro events—such as dividend changes, leadership transitions, or regulatory decisions—allowing wealth managers to identify potential risk inflection points earlier.

Importantly, this does not imply higher turnover or short-term trading. The role of AI in this context is informational, not prescriptive. It supports fiduciary decision-making by:

This reflects a broader shift in wealth management: from static portfolio construction toward continuous risk governance, where data augments—not replaces—professional accountability.

Because titles are unregulated, credentials matter. Common designations include:

Investors should verify credentials directly with issuing bodies and confirm regulatory registrations through SEC IAPD and FINRA BrokerCheck.

The appropriate choice depends on complexity, not status.

A financial advisor may be sufficient if:

A wealth manager is typically appropriate if:

The difference between a wealth manager and a financial advisor is not marketing—it is structure, obligation, and process. Wealth management is defined by holistic planning, fiduciary governance, and increasingly, by disciplined use of data to manage risk across time.

As the industry evolves, the most effective wealth managers are not those who promise outperformance, but those who combine human judgment, regulatory rigor, and modern analytical tools to preserve and compound after-tax wealth across generations.

It depends on complexity, not just net worth.

Many people start with a financial advisor and move to wealth management as assets and complexity grow.

The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but there are practical differences.

Wealth management is typically more comprehensive and more expensive, reflecting the added scope.

They serve different purposes.

For wealth management, a CFP is often more relevant, while CFAs are common in investment-focused roles. Some advisors hold both.

Yes. $500,000 is a common minimum for many advisors.

At this level, clients often receive:

The value typically comes from planning and discipline, not stock picking.

It may be possible, but it depends heavily on spending needs and other income.

Considerations include:

$400,000 alone may be tight without additional income, but it can work when combined with Social Security, part-time income, or lower expenses.

The 80/20 rule is an observation, not a requirement.

It suggests that:

For clients, it’s reasonable to ask how service levels are structured and what ongoing attention looks like at your asset level.

Join LevelFields now to be the first to know about events that affect stock prices and uncover unique investment opportunities. Choose from events, view price reactions, and set event alerts with our AI-powered platform. Don't miss out on daily opportunities from 6,300 companies monitored 24/7. Act on facts, not opinions, and let LevelFields help you become a better trader.

AI scans for events proven to impact stock prices, so you don't have to.

LEARN MORE